Back in January, the Corporation for Enterprise Development (CFED) published a powerful report on the financial health of America’s citizens. The picture they chose for the report’s cover describes the situation perfectly:

This report – The Assets & Opportunities Scorecard – covers all the basic elements that affect a family’s quality of life: education, housing, jobs, income/wealth, and healthcare. This report also breaks down the differences between how the past 6-8 years have gone for many African-American families, and how other American families have fared in these years of recession-recovery.

The numbers are not pretty. In fact, the numbers are scary…and yet familiar, particularly for Americans who live at the intersection of poverty and Black identity.

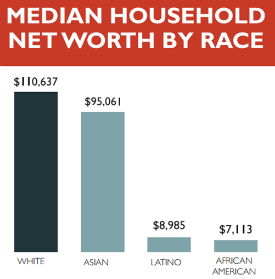

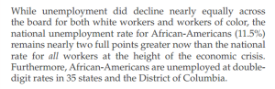

This is the stat that gets me every time. This graph doesn’t tell the whole story about the relative influence, power, and opportunities of the various racial/ethnic groups in America; but it certainly does introduce the main character and plot.

We know the single largest contributor to household wealth in America is home ownership. The Assets and Opportunities Scorecard includes a section that analyzes the challenges to (and potential solutions for) increasing the number of Americans who own their own homes. However, that’s not my primary concern. I’m more interested in thinking about how our current market-based system for valuing homes seems to have a structural flaw that will prevent African-American homeowners from increasing their wealth.

The thinking goes something like this: A house is only worth what somebody else is willing to pay for it. What somebody else is willing to pay for a house depends on several factors, including who is currently living in the house and who is living next door. Due in part to the lingering effects from historically government-sanctioned tactics of exclusion, restriction, and discrimination in the housing market, the majority of Black people in this country live in communities where most of their neighbors are also African-American. (If you’re interested in learning more about how our country’s racial politics has impacted how and where we live, check out the seminal book, American Apartheid by Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton)

For reasons that are beyond the scope of this post, Americans from non-Black racial/ethnic groups have not been willing to pay a premium to live in areas with a stable Black population. The only time Black people’s houses seem to go up in value is when they are moving out of an area en masse (i.e. urban gentrification). So one of the issues we have to wrestle with is, if the only people who are willing to pay top-dollar to live next to Black people are other Black people, then the values of Black-owned homes are unfairly dependent on the number of Black people who can afford to pay more for the house than its current owner did.

And if Black Americans’ wealth is directly linked to the value of their homes, then we have the uniquely tragic distinction of being the only group of people in America whose wealth-building opportunities are limited by economic poverty of our own people.

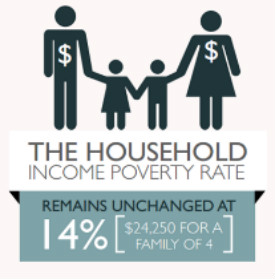

14% is about one out of every seven households in America. For those of us who live in urban or suburban areas in the country, the idea of looking at the houses/apartments next to ours and knowing that we would only need to count to seven before finding a family living in poverty should be profoundly troubling.

But that would actually be a much more manageable problem than the one we actually have now. What has become increasingly common is that we’ve created whole neighborhoods, towns, and even cities whose residents are all from that 1 in 7 household.

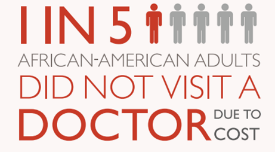

And that has real consequences:

Life-altering consequences:

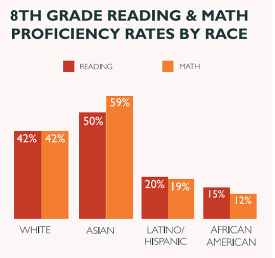

Future-determining consequences:

As we enter a season of reflecting on the promises made in previous elections, and the promises being made in our current elections; reports like CFED’s Assets and Opportunity Scorecard should be at the forefront of conversations about our vote.

Please do not entertain anyone who shows up at your school, in your church, in your barber/beauty shop, on your college campus, at your music festival, in your social media feed, or on your television screen who has not first demonstrated an understanding of the issues raised in this report, and a clear plan for using the tools of government to empower you to secure a brighter economic future.

– Day G.

Host, Class of Hope & Change