This is the fourth in a series of posts in which I try to understand what’s going on in our country right now.

Part 1 of this series looked at some of the questions facing Americans of various ethnic and racial groups. Part 2 examined the American public’s fascination with Pope Francis, and explored how our understanding about power and influence may be affected by his actions. Part 3 looked at the American Dream and the Gospel of Doubt.

Like many of you, I am already over this presidential election campaign. I am discouraged that a country which runs many of the world’s best sports championship tournaments relies on a system so flawed to determine who wins the job of U.S. President.

I often say that I am less interested in talking about what the candidates are doing, and I am more interested in trying to understanding what American voters are thinking. There are many groups of Americans who have some political soul searching to do in this moment. Including Black folks.

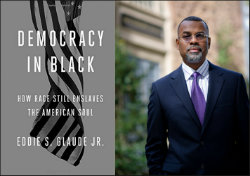

In 2016 several books written by Black scholars have begun to wrestle with the lasting implications of the gap between our 2008 hopes and our 2016 reality. Princeton University Professor of both Religion and African-American Studies, Eddie Glaude Jr., is the author of Democracy in Black – a powerful examination of the political, social, and economic experience of Black America in the age of the nation’s first Black president.

“This book offers a thicker description of the current state of black America. It shows how what I call the value gap (the belief that white people are valued more than others) and racial habits (the things we do, without thinking, that sustain the value gap) undergird racial inequality, and how white and black fears block the way to racial justice.”

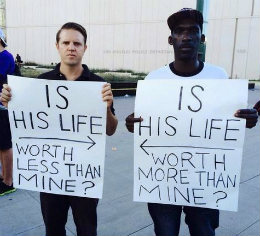

The quality-of-life matchup of Black America vs. White People is a frequent reference point for Professor Glaude throughout this book. As I considered his points, I kept wondering which belief is more harmful to Black folks (in America and around the world): The value gap as defined by Glaude above, or its corollary, which is the belief that Black people are to be valued less than everyone.

These two socially violent beliefs also affect how we understand the concept of racial inequality. The question underlying Glaude’s explanation of the value gap is, how much does our individual and collective understanding of racial equality depend on how we understand what race is. Do you think of race as simply a tool of human taxonomy, a method for describing the biological diversity of the human species? Or does the construct of race exist primarily to determine who is on the bottom of the social pecking order? In other words, does “Black” simply refer to people with some combination of biological traits? Or does the very definition of Black mean to be “less than”?

“Fast-forward to the Great Black Depression of 2008. Much of the gains of the 1990s were erased. African Americans lost 31% of their wealth between 2007 and 2010. White Americans lost 11%. By 2009, 35% of African Americans households had zero or negative net worth…One of out three black children grows up in poverty…one out of five black children is growing up in extreme poverty…In 25 of the 50 states and in the District of Columbia, at least 40% of African American children are poor.”

Whenever we come to the wealth/education/life gap conversations, we assume that we are working with a common set of category definitions. We are not. The first question I always ask before engaging these frightening and consistently depressing statistics is: Who is included in the definition of White American? I began to delve into this discussion in a previous post, but for the purposes of this post I am not as interested in how the circular pegs of Americans’ ethnic heritages are fit into the square openings of America’s racial boxes.

Instead, I think the stats above effectively illustrate the value gap that is the central theme of Professor Glaude’s book. There are many capitols around the world where abject poverty exists alongside wealth, power, and privilege. There are many cities in America where children of numerous racial and ethnic groups struggle in communities stuck between have-not-at-all and have-not-enough.

Glaude challenges us to deal with what it means if the suffering, failure, and lack among Black Americans is a core design element – instead of an operational malfunction – in the machine of American society. These statistics expose the perception gap between those who believe America is like a strong sports league where each team has an equal shot at a winning season if they make the right moves; and those who see America as a fragile league that is structured to ensure that only a handful of teams will ever be really good, and that some teams will always be at the bottom of the rankings.

“Because racial habits are hidden in plain sight, most of us deal openly with race only when some ugliness bubbles up…We mistakenly think that the resolution of our race problems occurs in these moments, but it doesn’t, largely because the way we deal with them as a society is more theater than substance…Racial theater is somehow the stand-in for actually confronting the problem…And we tell ourselves after watching the special or listening to the conversation that we are all better people for doing so – that we are, at least, a bit less racist. But our racial habits remain completely intact.”

This idea of racial theater is such a helpful analogy as we move through these next four and a half months of national political campaigning. Much of the discussion on cable news and social media is built on a binary “they are evil / racist / bigots / ____phobic, but we are good” framework. Time and time again Democracy in Black troubles the waters, revealing the ways in which we are all complicit in the oppression of our fellow citizens.

In a moment when some of the country’s most visible celebrities, politicians, and celebrity politicians seem to go out of their way to serve up easy-to-condemn caricatures of hate; it is important for the rest of us to not be deceived into thinking that a stance against them is the same as progress.

This week began with the tragic and frightening mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Many people from the LGBTQ community have rightly called out the hypocrisy of politicians and others who were crying and praying for people whose lives they actively sought to diminish. These critiques have been joined by voices challenging the self-righteous condemnations of immigration bans against Muslims from politicians who used the false rumor that President Obama was Muslim to depict him as something other than American. We can go further and raise questions about how well the progressive/liberal principles of tolerance, social justice, and equality are being lived in the communities on the front lines of the unrelenting march of gentrification.

In other words, there are no pedestals for us to stand on. There are no superhero capes for us to don. The work of living and speaking truth is both outward (“at them”) and inward (“to us”). Professor Glaude has helped to describe the “value gap” script which directs so much of life in America. Questioning, discarding, editing, and rewriting that script will require more of us than we have given before.

Back to work.

– Day G.

Host, Class of Hope & Change