“Wouldn’t you know / We been hurt, been down before /

When our pride was low / Lookin’ at the world like, ‘where do we go?’…

But we gon’ be ALRIGHT! …Do you hear me, do you feel me? We gon’ be alright”

Just when I thought we couldn’t squeeze any more juice from the abundant fruit in Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly album, the California rapper dropped the video for Alright in June. The song’s chorus has served as the hip-hop spiritual of the summer…a musical antidote to the parade of social trouble that has claimed lives in communities across the U.S.

Although our country has witnessed three consecutive years of nationwide protests and petitions… and despite week-after-week of televised debates and demonstrations…it feels like we are stuck in a narrative about Black communities that revolves around suffering, tragedy, wasted government assistance, failed local leadership, violence, and death.

But this narrative is not new. We have heard it before…

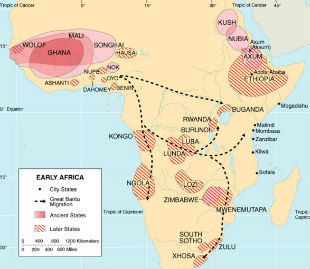

There are numerous parallels between the reductionist narratives that have developed around both Black America and Sub-Saharan (Black) Africa. Black America is often talked about as if all of its nearly 50 million members live on the same block, were raised within the same family structure, and move through the world with the same economic resources. Similarly, the nearly one billion people who live on the continent of Africa, who represent 54 countries and thousands of ethnic/tribal groups, are often discussed as if they are part of the same country, speak the same language, and share the same traditions and customs.

There are very few groups of people on the planet who have had as little say in the global understanding of their past, present and future as people of African descent…whether they live in the U.S. or on the continent. In the U.S., we are seeing a new generation of young people fighting to be seen in their full humanity by their fellow citizens…while wrestling with what it means to truly see each other.

For many young people in this generation, it is becoming clear that a few tweaks to our nation’s laws will not be enough to address the deeper questions about how “We the People” can improve the way we relate to each other. I would argue that many of us will not be able to engage the full meaning of #BlackLivesMatter without a fundamental re-formation of our ideas about who and what constitutes “Black”.

For that…we’re going to need new maps…

For the past few centuries, much of what we know about Africa has come to us through the stories told by those who saw themselves as conquerors and colonizers. The same can be said for the lens through which information about Black American history and life has been presented to the world. As a result, for many Americans, the story about who Black people are begins with some version of, “First they were slaves.” This makes it difficult for some of our fellow citizens to accept the dignity and humanity of Black people as a Self-Evident Truth rather than as a limited time offer granted by a benevolent nation.

What if we could learn to see people on their terms? What if we could learn to see people through their lives and their imaginations rather than through their deaths and their sufferings?

Enter this wonderful book, The Bright Continent, from Nigerian American journalist Dayo Olopade. Her book is a deep look at the creativity, innovation, and resourcefulness of people and communities in countries all over Africa. Every chapter contains information you never knew, innovations you never thought of, and opportunities you never knew existed. Olopade’s gift to us is to shake our mental Etch-a-Sketch (younger readers see below) about life in Africa, disrupting and erasing the lines our minds have drawn around the continent…giving us the space to draw something new.

Olopade’s book draws a new map of Africa, one based on the regions of Family, Technology, Commerce, Nature, and Youth. Her research and writing help to move us away from a safari approach to thinking about Africa (which parallels the way many people approach Black American culture). Dayo revels in what she terms the spirit of “kanju – the specific creativity born from African difficulty” that she saw in each country she visited. The accounts of kanju in her book come from the time she invested living… sitting… walking… and talking… with people.

A few examples from her book:

“The most impressive example of modern diaspora engagement must be Dahabshiil, a money transfer service born in Somalia. The company allows users to drop off cash in Minneapolis and pick it up in Mogadishu or Mumbai – and the other way around. Abdirashid Duale, the Dahabshiil CEO, manages billions of dollars in international remittances…The business has expanded to 144 countries and the platform now enables Ethiopians, Sudanese, Rwandans, and Ugandans to send money around the world.”

“As caretakers, laborers, decision makers, or entrepreneurs (at least some of the time), Africa’s women are overlooked brokers of behavioral revolutions. It’s impossible to talk about women and social networks in Africa without describing Tostan, an advocacy group that has nudged thousands of communities in Senegal and the Gambia to stop the practice of female genital cutting.”

“In sub-Saharan Africa, secondhand clothes are bad for business…When bales of free clothing flood local markets, they put tailors and clothiers and textile laborers out of work…For many families getting free TOMS shoes, a steady job – making say, shoes – presents a more permanent solution…Bethlehem Tilahun Alemu, owner of soleRebels, exports shoes from Ethiopia – whose shoemakers are among the biggest producers on the continent.”

“Nollywood is second-ranked in the number of movies it produces – up to two thousand per year – and among the world’s top revenue generators – $250 million annually by some estimates…Nollywood movies and soap opera serials, produced on the cheap and sold locally as home videos (only a handful ever meet a silver screen), are known for melodrama, rolled eyes, waggling necks, and pointed fingers…the key innovation of Nollywood was never making movies…Rather, Nollywood’s innovation was customizing film offerings for a local audience.”

“Take the example of Ushahidi, the Kenyan nonprofit that sprang up in the aftermath of the nation’s contested 2007 presidential election…First by blog, then by email, then in person, a team of Kenyan techies began working on a mapping application that allowed citizens to report violence using their cell phones. Thousands of data points shared using Ushahidi – which means ‘witness’ in Swahili – produced a map with real-time, geo-specific information that sped the effort to restore order and provide relief services.”

For those of us who are engaged in work of fighting for justice, equity, and opportunity for marginalized people in the U.S., Dayo’s book gives us a template for documenting the vast range of human capital that exists among Black people all over our own country.

We must continue the work of redrawing the mental maps of what Black is and can be. We must continue to create social maps that reflect the lives the talents, aspirations, and imaginations of Black people everywhere.

– Day G.

Host, Class of Hope & Change