In a 2009 TED Talk called How to live to be 100+, National Geographic writer Dan Buettner discussed some of the findings from a long-term study conducted by the magazine to uncover “what really helps us live longer better.”

The magazine’s researchers identified several “Blue Zones” – demographic and geographic areas where people live longer and healthier lives. 800 miles south of Tokyo, on islands of Okinawa, the researchers met a community of people whose quality of life statistics are incredible. Okinawa has been home to several of the world’s oldest living women, and five times as many centenarians (people over 100 years old) as the United States. Residents there have longer life expectancies without chronic disease and much lower rates of cancer.

Mr. Buettner explained some of the behaviors and values that are allowing so many Okinawa residents to win at life. He talked about their plant-based diet, their strategies for not over-eating, their social structures (“Moai” refers to a lifelong group of friends who they see and visit with on a daily basis), and the fact that they don’t have a word for retirement.

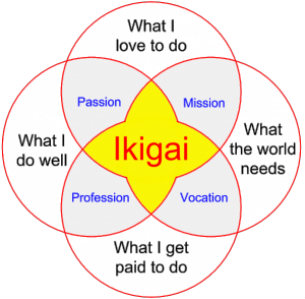

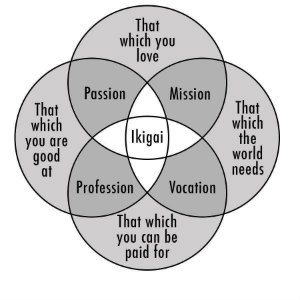

Of all the concepts he talked about, the Okinawan principle of Ikigai (“EE-Key-Guy”), which translates to “the reason for which you wake up in the morning”, has been a favorite of audiences here in the U.S.

The diagram above illustrates the principle of Ikigai. I was so moved by the power of the ideas expressed in this interlocking Venn diagram, that I’ve decided to make it my cell phone lock screen photo for the next 30 days to help keep these ideas at the front of my mind.

What Do You Do Well?

Depending on your life experiences, particularly the type of feedback you received from adults as a child, the first question may be ‘is there anything I do well?’ Some of us still carry the emotional weight of negative comments adults placed on us and we have trouble identifying our own strengths. The issues of self-worth and self-love are critical before trying to engage any of the other ideas included in the principle of Ikigai.

Who measures ‘well’? In the U.S., we tend to focus on the talents and skills that are revealed in youth. The child piano prodigy. The young tech genius. The 12-year basketball player dunking a ball in middle school. The adorable tween actors on TV sitcoms. We are asked to choose a life path and profession at 18. We set arbitrary age markers for when we should be “established”.

And then there’s the effect of social media on our perceptions of our own skills. It’s no longer enough that I do something well, if I see people on my phone who seem to be doing it better than me. There is a fine line between being inspired and motivated by others, and falling into an unhealthy practice of trying to find where you are by looking at someone else’s life map.

It’s important to give ourselves the space to continually discover what we’re good at. To accept the fact that our definition of good might need to change. To be honest about any psychological baggage we carry with us that places limits on what we think we can do. We need to surround ourselves with people with whom we feel safe to explore, experiment, and discover. We need friends who help us to expand our perception of what we can do.

What do you love?

This one is tricky because, for many of us, what we love to do changes over time. Even if the things we love haven’t changed, sometimes the amount of time we love to do those things changes. I used to love playing basketball from dawn ’til dusk. Now, I’m good after 3 full-court games. If I had to play basketball all day, every day at this season in my life, my love for the activity would fall dramatically.

As with our sense of what we’re good at, what we love to do is also socially contextual. Sometimes we love something because we love the impact/effect it has on other people. Chefs love how good food brings people together. Teachers love how students’ eyes light up when they’ve learned something interesting. Realtors love handing people the keys to their first homes.

What happens when what you love is not considered age-appropriate for you anymore? A dancer in her 40s is treated differently if she dances for Alvin Ailey than if she dances in a hip-hop music video. A singer who wants to keep making love songs in his 50s is received differently than if he wanted to keep rapping.

“Do what you love” is not always as straightforward as it seems. Again, we have to be honest with ourselves about what brings us happiness and how much that happiness depends on other people’s reaction to us.

What does the world need?

This is an interesting question in our current “isn’t there an app for that?” society. If we measure what we need only by what we are willing to pay for, then it can end up looking like the only things we need are someone to drive us around, someone to deliver stuff to our homes, and someone to be our on-demand bae. I’m sure someone reading this is thinking, “what else do you need, really?!”

However the world needs a lot more. How much we see of the world’s needs depends in large part on how much we see “our world” intersecting and overlapping with “the world”.

When you think about what the world needs, how many of the following would be on your list?:

- Healing and reconciliation

- Justice and equity

- Clean water, food, air and energy

- Love and compassion

- Friends and family

- Freedom and liberty

What do I get paid to do?

In most of the developed countries of the world, particularly those countries based on capitalism, this is the most important question. For many people in these societies, this is the reason schools exist. When adults ask children, “what do you want to be when you grow up?”, what they are really asking is a gentler version of “sooo, what are you going to do for money?”

In the U.S., your paid occupation is the top line of your life’s resume. If you’re telling friends and family about a new person you’re dating, one of the first questions you will get is “so, what does he/she do?” If you’re chatting with someone in the next seat on an airplane, we often mention our job titles before we mention our names. When politicians and advertisers are trying to identify which groups of people to target with their message, our occupations are an important category in their calculations.

As is often the case in conversations about money, the most important questions are: Who has the money? & Who decides who gets the money? As we see with the age-old ‘vice industries’ of drugs, alcohol, and sex; it matters a great deal who is paying for the service.

What happens when people are wiling to pay for something, but they are not willing to pay you for it? In this question, we consider all the various forms of preference, bias, and discrimination that we all engage in everyday. Will you let anyone cut your hair who has a license to do so? Will you drop your children at a daycare run by anyone who is licensed in your state? Will you watch a TV show starring anyone who is a professional actor? Will you move to any part of town that has available housing? And on and on…

Last, but not least, what happens if you can’t get paid enough to do something. Here I’m thinking about home healthcare workers, restaurant workers, and everyone else who has a passion, a mission, and a vocation…but doesn’t make enough to have a profession.

This concept of Ikigai is a powerful one, not just for each of us individually, but for our families, communities, and our country collectively. We’re going to need some fresh thinking, and a re-ordering of our priorities to create a world where more people are fully living out their purpose.

– Day G.

Host, Class of Hope & Change